When is an Idea too Abstract to Pass the Patent Eligibility Test?

By Babak Akhlaghi on October 4, 2023.

In Free Stream Media Corp. v. Alphonso Inc., Case No. 19-1506 (Fed. Cir. May 11, 2021) (Reyna, J.), the Federal Circuit held claims toward a system for delivering relevant advertisements to a mobile phone user based on data collected from their television are not patent eligible.

In November 2015, Samba TV sued Alphonso for infringement of U.S. Patent No. 9,386,356 (“the ‘356 patent”). Alphonso responded by filing a motion to dismiss, arguing that the patent claims were ineligible under § 101. However, the district court disagreed with Alphonso’s argument, stating that the claims were not directed to an abstract idea. Alphonso then appealed.

The ‘356 patent is titled “Targeting with Television Audience Data Across Multiple Screens” and describes a system that delivers relevant advertisements to a mobile phone user based on data collected from their television. The patent’s claims involve three key components: a networked device (e.g., a smart TV), a client device (e.g., a mobile device), and a relevancy matching server.

Representative claim 1 recites:

- A system comprising:

a television to generate a fingerprint data;

a relevancy-matching server to: match primary data generated from the fingerprint data with targeted data, based on a relevancy factor, and search a storage for the targeted data; wherein the primary data is any one of a content identification data and a content identification history;

a mobile device capable of being associated with the television to: process an embedded object, constrain an executable environment in a security sandbox, and execute a sandboxed application in the executable environment; and

a content identification server to: process the fingerprint data from the television, an communicate the primary data from the fingerprint data to any of a number of devices with an access to an identification data of at least one of the television and an automatic content identification service of the television

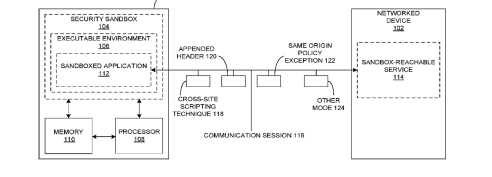

The client device has a security sandbox in place, which acts as a security mechanism to separate running programs. According to the specification, this security sandbox can restrict what applications are allowed to do. For example, it can limit network access, making it challenging for the client device to connect to the user’s networked device and obtain information from it. This information may include the currently playing content on the networked device. The specification explains that the security sandbox can be bypassed by establishing a communication session between the sandboxed application and the sandbox-reachable service of the networked device. This can be done using cross-site scripting, an appended header, a same origin policy exception, or other methods to bypass the access controls of the security sandbox. Figure 1 provides a visual representation of how this communication session is established.

U.S. patent law allows patents for processes, machines, manufactures, and compositions. However, there are exceptions. Laws of nature, natural phenomena, and abstract ideas are not eligible for patents. To determine if an invention is eligible, we follow a two-step process established by the Supreme Court in the Alice case. First, we check if the claims are directed towards patent-ineligible concepts. We consider the focus of the claimed advance compared to prior art and the specification. If the patent is determined to be directed towards an abstract idea or ineligible subject matter, we move on to the second step. In this second step, we analyze the elements of each claim individually and as an ordered combination to see if they transform the nature of the claim into a patent-eligible application of the ineligible subject matter.

Here, the district court determined that the asserted claims were not directed towards patent-ineligible subject matter, but the Federal Circuit disagreed, holding that the claims were indeed directed towards the abstract idea of targeted advertising.

Reviewing the ‘356 patent, the Court noted that claim 1 focuses on gathering information about the viewing habits of television users, matching that information with relevant content (such as targeted advertisements), and sending that content to a mobile device. Samba argued that these claims represent an improvement in computer capabilities, specifically in how television and mobile devices interact with each other. It argued that its invention is similar to previously eligible inventions in Enfish, Visual Memory, Finjan, Core Wireless, and Uniloc. Samba further argued that the claimed advancement lies in sending relevant content to a user’s mobile device through a sandboxed application. When questioned about how claim 1 achieves this, Samba’s counsel explained that the embedded object provided by the relevancy matching server allows the phone to bypass the sandboxed application. Specifically, the Court noted that Samba’s purported claimed advance lies in the following specific limitations of claim 1:

a mobile device capable of being associated with the television to: process an embedded object, constrain an executable environment in a security sandbox, and execute a sandboxed application in the executable environment . . . [;]

a content identification server to: process the fingerprint data from the television, and communicate the primary data from the fingerprint data to any of a number of devices with an access to an identification data of at least one of the television and an automatic content identification service of the television.

The Court was not persuaded this advacenemtn is enough. In the cases Samba relied upon, the Court had determined eligibility because the claims in question involved specific improvements to computer functionality. For example, in Enfish, the focus of the claims was on improving computer functionality itself, rather than on economic or other tasks. In order to assess eligibility at Alice Step 1, a key consideration is whether the claims focus on specific means or methods that enhance the relevant technology, or if they merely invoke generic processes and machinery. The claim must identify how the functional result is achieved through concrete structures or actions. In this case, Samba’s claims to enable communication between devices on the same network that were previously unable to do so. However, the claims do not provide a clear description of how this is achieved. While the specification mentions mechanisms like piercing the security sandbox, it does not explain how this is done. The specification only mentions using computer security vulnerabilities or relaxing rules, but these methods are not included in the claims. Therefore, the asserted claims do not incorporate any specific methods of piercing the sandbox.

Furthermore, although Samba claims that its invention leads to televisions and mobile devices operating differently from conventional devices, the Court noted that it does not explain how this improves the functionality of these devices beyond providing targeted advertising using generic processes and machinery. Samba’s claims only improve the abstract idea of targeted advertising. Since Samba’s claims do not involve an improvement in technology or the creation of new computer functionality, the Court held that they are ultimately directed towards an abstract idea.

Turning its attention to step two of Alice, the Court held that the elements of the claim individually and as an ordered combination do not transform the nature of the claim into a patent-eligible application of the abstract idea. Samba, in its argument, referenced two earlier cases, DDR Holdings, LLC v. Hotels.com, L.P., 773 F.3d 1245 (Fed. Cir. 2014) and BASCOM Global Internet Services., Inc. v. AT&T Mobility LLC, 827 F.3d 1341 (Fed. Cir. 2016). Samba asserted that the claims of the ‘356 patent, like those in the aforementioned cases, describe the components and methods that allow unconventional operation of televisions and mobile devices, including fingerprinting, content identification servers, relevancy-matching servers, and bypassing mobile device security. This patent enables the intermediation of communication between the two devices to obtain information about television content that can be provided to the mobile device, bypassing its security sandbox.

In DDR Holdings, the claimed invention solved the issue of visitors to a website being forced to leave the site when activating hyperlinked advertisements. The claims described an invention that went beyond the routine or conventional use of the internet. In BASCOM, the court determined that an inventive concept could be found in a non-conventional and non-generic arrangement of known pieces. Here, sandbox security restricts communication between internet-connected devices. The claimed invention seeks to overcome this by bypassing the mobile device security mechanisms. However, the mere bypassing of the client device’s sandbox security describes the abstract idea of providing targeted content to the client device.

Even if the bypassing of mobile device security mechanisms hadn’t been done before, there is nothing inventive in the claims that allows previously impossible communication. The claims simply describe the use of generic features and routine functions to implement the underlying idea. An abstract idea is not patentable if it does not provide an inventive solution to a problem in implementation. The Court noted that the claims in this case employ conventional components, as well as routine functions, to implement the underlying idea. Therefore, the Court held that the claims also fail the step two of Alice and are therefore patent ineligible.

Connect with me on LinkedIn to stay updated on the latest patent news and update. Looking forward to connecting with you! Subscribe to our Newsletter