Cracking the Code: Understanding Obviousness Challenges and the Motivation to Combine Prior Art

By Babak Akhlaghi on August 8, 2023.

The Federal Circuit reversed the Board’s non-obviousness finding, holding that the key question in obviousness determination is whether a skilled artisan would be motivated to combine different references to achieve the claimed invention not the references. Axonics, Inc. v. Medtronic, Inc., Case No. 21-1451 (Fed Cir. July 10, 2023) (Lourie, Dyk, Taranto, JJ.)

Medtronic holds two patents, 8,626,314 (“the ’314patent”) and 8,036,756 (“the ’756 patent”), which cover a neurostimulation lead and a method for implantation and anchoring of the lead. Medtronic sued Axonics for infringement of both patents. Axonics responded by challenging the validity of certain claims in these patents. The Patent Trial and Appeal Board of the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office rejected Axonics’ arguments and found the challenged claims to be valid. Axonics appealed.

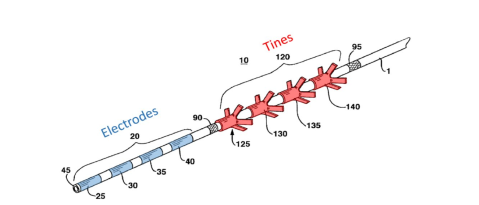

The ’314 patent is a grandchild of the ’756 patent and deals with stimulating sacral nerves for the stimulation of body tissue. It involves an implantable medical electrical lead with a stimulation electrode near the sacral nerves, along with a fixation mechanism for stability. While the patent focuses on sacral nerve stimulation in the “Field of the Invention” section, it is not limited to that area as pointed out in the other sections of the patents. Furthermore, the patents’ claims don’t mention sacral nerves. The patents highlight key features, including multiple electrodes and tine elements for stability. Figure 2 of ’314 patent shows an example of the electrode array and tine elements.

Axonics filed a petition on March 16, 2020, requesting inter partes reviews (“IPRs”) for certain claims of the ‘314 and ‘756 patents. In its petition, Axonics argued that the challenged claims were obvious under 35 U.S.C. § 103 based on the combination of Young (a 1995 study) with U.S. Patent No. 6,055,456 (“Gerber”) and PCT App. No. WO 98/20933 (“Lindegren”). Specifically, Axonics argued that Young’s single electrode could be replaced by multiple electrodes at the distal end, as taught in Gerber, to provide more flexibility and the possibility of bipolar electrical stimulation. Axonics also highlighted Young’s statement that the neurostimulator used in the study could be improved to have multiple active stimulation sites near the tip. Additionally, Axonics pointed out that Gerber disclosed multiple electrodes on implanted leads for sacral nerve stimulation and an anchoring mechanism that fixes by fibrosis.

In its final written decision, the Board determined that all challenged claims of the ‘314 patent were not unpatentable based on obviousness. Axonics appealed.

The determination of obviousness in a legal case involves various factors, such as the prior art, the level of skill of an artisan, and whether there is motivation to combine references to achieve the claimed invention. In this particular case, Axonics’s challenge was rejected because Axonics could not demonstrate that there would be motivation for an artisan to combine the teachings of Young and Gerber. The Board based this rejection on the fact that the proposed combination of Young and Gerber would not be feasible because Young’s was focused on electrode improvement in the trigeminal nerve region and not in sacral nerve region as suggested by ‘314 patent and Gerber. Medtronic and its expert, Dr. Slavin, argued that Young’s suggestion of adding electrodes was not feasible due to the complex anatomy of the trigeminal nerve region. However, the Federal Circuit found that this reasoning was flawed.

Firstly, the Board erred by limiting the motivation inquiry to the specific context of the Young trigeminal-nerve, while the Medtronic patent claims were not limited to that context. Secondly, the Board was incorrect in stating that the relevant art was limited to sacral nerves. Therefore, the Board’s decisions were vacated and the case was remanded.

When evaluating an obviousness challenge that involves a combination of prior art, the key question is whether a skilled artisan would be motivated to combine different references to achieve the claimed invention. It is important to focus on combining features that are relevant to the claims being considered, rather than meeting requirements of a reference that are not relevant. This aligns with established principles, as the claim defines the invention being assessed for obviousness. A skilled artisan may have motivation to combine different features from various references, even if bodily incorporation is not possible or advisable, in order to obtain specific benefits. The crucial question, as stated by Medtronic, is why an artisan would combine elements from specific references in the same way as the claimed invention.

The Board made a legally incorrect framing of the motivation-to-combine question by confining the inquiry to whether a motivation would exist to make the Gerber-Young combination for use in the Young-specific trigeminal-nerve context. However, this context is not part of the claims of the Medtronic patents. The proper inquiry should be whether the relevant artisan would be motivated to make the combination to meet the actual limitations of the claims, which are not limited to the trigeminal-nerve context. The Board’s view contradicts its own definition of the relevant artisan and the problem addressed by the Medtronic patents. The relevant artisan, focused on the problem of sacral-nerve stimulation, would consider what Young taught or suggested about combining features with Gerber for the sacral-nerve context, not just for the trigeminal-nerve context.

Therefore, the Board improperly limited the analysis of the Young-Gerber combination to what would work in the trigeminal-nerve area. Additionally, the Board made an error in defining “the relevant art” as limited to medical leads for sacral-nerve stimulation. The Medtronic patent claims do not specify sacral anatomy or sacral neuromodulation, and they should not be construed as so limited. Treating the relevant art as a narrow subset of what the claims cover would curtail the analysis of prior art and limit the scope of the claims. It has been ruled that “analogous art” for section 103 purposes is determined by “the claimed invention”.

A Practice Tip: A strong rebuttal to the determination of obviousness is to highlight how the combination of the prior art references actually teaches away from the claimed invention. In this case, the patent owner mistakenly argued that one prior art reference teaches away from another prior art reference. However, the crucial question in evaluating a teaching away argument is whether the combination of references teaches away from the claimed invention, not just the specific prior art reference being examined.