How to Patent an Idea?

By: Babak Akhlaghi

June 29, 2020

In this article, we will focus on how to patent an idea. The goal of the patent law is to promote progress of science. Its basis is found in the U.S. Constitution, Article 1, Section 8. Patent law encourages inventors to disclose their inventions to the public. In return, the government protects the inventions for 20 years. U.S. patents are available for technologies that are useful, new, and unobvious. However, ideas such as processing mathematical algorithms or performing activities that could otherwise be performed by humans cannot be patented. They are considered abstract.

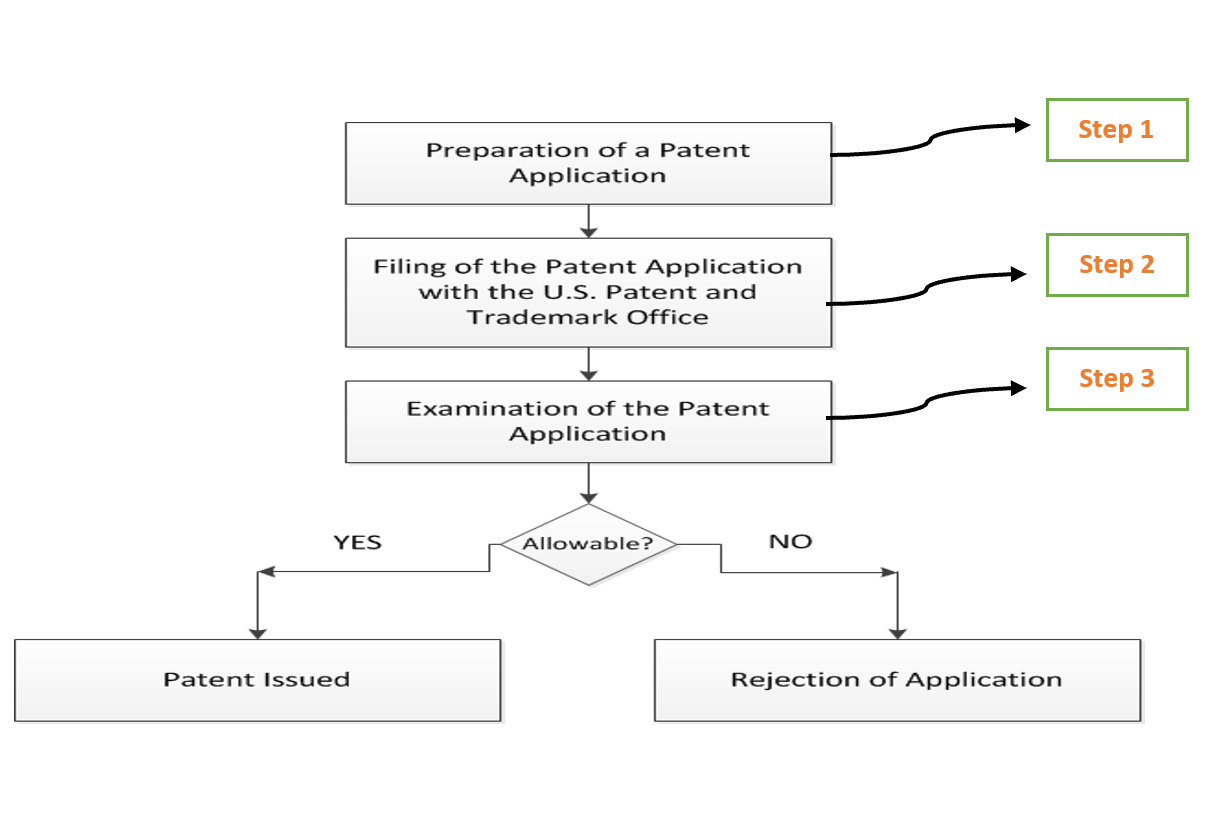

Reproduced below is the process for obtaining a patent:

The process begins with preparing a patent application. Obviously, you need an idea. However, after you have your idea, you need to identify a registered patent practitioner to prepare a patent application for your idea. A registered patent practitioner is normally a registered patent attorney. Patent attorneys have two licenses: one general license issued by the state bar in which they practice law and one license issued by the United States Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”). To obtain the USPTO license, the patent attorney must have a scientific background with a minimum of a bachelor’s degree in Engineering or another scientific field. They must also pass the Patent Bar Exam administrated by the USPTO.

Once you have identified and engaged a suitable patent attorney for your invention you can then disclose your idea to them. Don’t worry about signing a non-disclosure agreement, also known as an NDA, with the patent attorney after you engage them. Your communications with the patent attorney are legally protected under the attorney-client privilege. The disclosure of your invention to your patent attorney can be done in 3 ways: 1) it can be done over the phone; 2) it can be done over video conference; or 3) it can be done in person. These days, most disclosures are done either through the telephone or video conference. I personally use Microsoft Teams for the majority of my disclosures. An invention disclosure normally takes about one hour. The patent attorney will ask you about how you will make and use your invention. It’s important to provide your patent attorney with any technical documents that you have describing the invention during or before the disclosure meeting. It is preferable to do it before the disclosure meeting so your patent attorney will be better prepared. It will also result in a more fruitful discussion between you and your patent attorney.

After the disclosure, your patent attorney may conduct a patent search to identify or assess the patentability of your invention. Basically, they want to make sure your invention is actually new. Assuming the patent search results are okay, your patent attorney will move forward to prepare a patent application for your invention. The patent application is both a technical document and a legal one. It describes the manner of making and using your invention and it also describes the boundaries of the invention. So, it is very important that your patent attorney has the relevant technical background in the field of your invention to fully describe your invention in the application. If he or she does not, then your application may be flawed and rejected.

Particular considerations must be made for applications on inventions relating to computer-implemented and software inventions. How the USPTO and courts handle such applications is still in flux. Accordingly, many applications on computer implementations and software have been rejected, and patents found invalid, because computer and software implemented inventions often fall into the category of “abstract.” Thus, care must be taken to characterize such inventions as being in a non-abstract technical field. Improving on a technology outside software or ordinary computer implementation, or doing more than performing an abstract function using more than standard computer components, is not considered “abstract.” A patentable invention may be an improvement to a computer itself, for example by improving data processing speed, reducing memory requirements or performing improved functionality in some other way.

A successful application in this field thus often will describe the invention as a solution to a specific technical problem involving the computer itself or to a technical improvement to some other environment. The disclosure and claims of the application should be presented in this manner, when possible. Other examples of patentable inventions in this field have been identified by courts, and are evolving.

The second step of obtaining a patent includes filing the patent application with the USPTO. This step involves submitting your application with formal documentation to the USPTO. These include an assignment, power of attorney, inventor’s declaration, and an application data sheet.

The third step is the examination of your patent application by the USPTO. During the examination, your application is assigned to a patent examiner who has the relevant background in the field of your invention. An examiner normally has many applications assigned to them so it could take a few years for the examiner to pick up your patent application and start reviewing your invention.

During the examiner’s review, they will conduct an online search to determine the patentability of your inventions. The examiner will set forth their findings in a written communication, which is referred to as an Office Action. An Office Action sets forth reasons for rejecting your application. To reject your application, the examiner usually relies on one or more references, such as prior patents or prior publications, and alleges those references teach your invention.

The examiner will mail the Office Action to your patent attorney. The Office Action must be responded to within three months, although up to an additional three months of time can be obtained for response by payment of a fee. The response must address all issues raised in the Office Action. An important component of the response is the “remarks,” which is a written statement explaining how the response has successfully addressed the rejections, with particular emphasis on how the invention is difference over the references found by the Examiner. You will work closely with your patent attorney to develop a strong technical argument supporting patentability of your invention. Care must be taken during this time to draft a strategic response because anything said becomes a part of the public record and can be used against your patent in the future.

The examiner, taking the response into consideration, may issue an allowance of the application for passage to issuance, or may issue a second Office Action if the response is found not to be persuasive. Alternatively, the second office action may be issued because, based on further searching, the examiner has uncovered new prior art addressing the points made in the response. This second office action often is made “final,” meaning that no further amendments considered substantive may be made. Further prosecution at this point will require either an appeal of the rejection or filing of a “continuation application,” requiring payment of another filing fee.

This back and forth between your patent attorney and the examiner is often referred to as the “prosecution.” Ultimately, the prosecution of your application will either result in an allowance or a final rejection of your application. If your application is allowed, it will go on to issue as a patent. However, if your application is rejected and all appeals are exhausted, then it will ultimately become abandoned.

Upon allowance of the application, an issue fee must be paid. The patent will issue within several weeks from payment. After issuance, maintenance fees, increasing in amount, must be paid at 3.5, 7.5 and 14.5 years from issuance.